[ad_1]

Australia’s higher education system has been one of the country’s hardest-hit sectors during the pandemic, as border closures have halved revenue for international student numbers.

Covid-19, and the government’s response to tighter border controls – part of its “Fortress Australia” policy – has stifled the flow of overseas students. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, revenue for universities, a vital resource, fell to A$20.2 billion ($13.8 billion) in the year to June. This compares to A$38.7bn for the same period in 2019 before the outbreak.

Universities and their business schools quickly devised ways to shift online courses and maintain connections with students who were detained and had no way back home. However, enrollment from overseas has fallen.

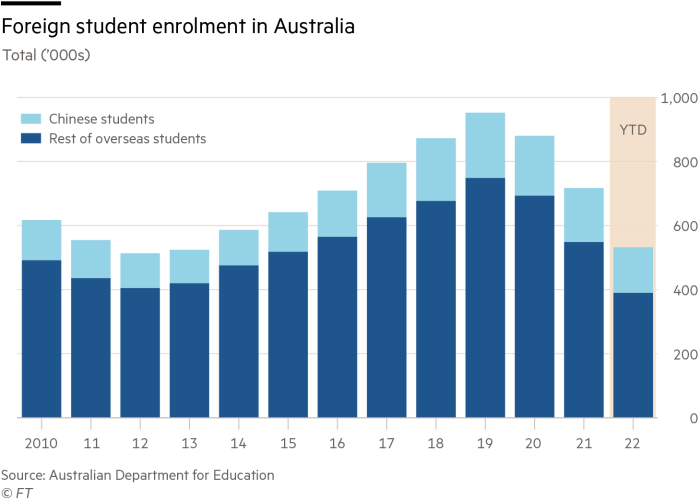

There were 956,773 international students enrolled at Australian universities in 2019, with more than 750,000 paying full fees on student visas, government figures show. That number is down to about 446,000 this year.

Eliza Lytton, an economist at the public policy think tank the Australia Institute, said the sector had become “more reliant on international student fees, day-to-day work and underpaid workers – problems exacerbated by the pandemic”.

In the year By 2021, Australian universities are set to record their first revenue decline in eight years, leading to 35,000 job cuts – almost one in five – in the higher education sector.

Former Professor Roy Green, dean of the University of Technology Sydney’s business school, said this would increase pressure on academic staff to improve their teaching. Meanwhile, research projects – often from international student fees – have been cut, prompting many graduate students and undergraduate researchers to go overseas. “It has led to depression in the higher education sector,” he added.

Geopolitical tensions between Australia and China have also hit universities that rely on a steady flow of international students.

In a speech at the University of Technology Sydney in June, China’s ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, sought to highlight the importance of educational ties between the two countries. He pointed out that there are 131,400 Chinese students in Australia, which accounts for 28 percent of the country’s international students.

35,000

The number of job cuts in Australian higher education due to the pandemic

This number, according to Australian government data, is up to 20 per cent lower than last year – an increase compared to students in other countries.

However, there are now signs that the Chinese students may return in force. John Chew, head of global insights at consultants Navitas, said visa data for the first six months of the year indicated a “complete recovery” in the number of Chinese students. About 40 percent of these were returning students.

But Chew added that New South Wales’ auditor-general had highlighted this reliance on Chinese fee-paying students. Seven out of 10 universities in the state say China is the primary source of foreign student income, posing a concentration risk.

Reduction in Chinese students The rise in student numbers from India, Nepal and Indonesia in recent years has been less pressing for business schools, reducing revenue for Australia’s biggest trading partner.

In addition, domestic demand unexpectedly increased during the outbreak. Mark Barnabas, who sits on the board of the Western Australian Business School and has been its chairman for nearly two decades, said business schools were unable to benefit from the country’s strict lockdown protocols.

“The domestic market has increased as people are isolated at home. [and] They chose to study during the lockdown,” he said. “Companies that want to retain labor also encourage that and help with pay. It was an unusual dynamic that benefited Australian business schools in general.

Andrew John, associate dean of Melbourne Business School, said that while the executive education business was down during the lockdown, the institution had one of its largest intakes of part-time students since September 2020. “This does not surprise us,” he says.

The main change at Melbourne Business School is a slower “study pace”, with fewer students taking two classes at once. “We’re not sure if this is temporary, perhaps at least coincidentally a reflection of the pressures and exhaustion felt in the workforce in Australia, or if it’s a permanent change,” says John.

Australia’s aim is to attract more international students to its shores, with plans to cut visa complexity – not only to increase numbers, but also to try to make more of them permanent citizens.

Student dropouts have become a source of threat to the higher education sector and the broader economy. If Australia loses its best overseas students but fails to retain international students after study, it risks a ‘brain drain’. At the same time, unemployment is at a 50-year low, and the country is facing a labor shortage.

The government has responded by extending visa stays and the right to stay and work for student visa holders as a key attraction for more international students to enroll.

Barnabas, who is also vice-chairman of mining group Fortex and sits on the board of the Reserve Bank of Australia, believes the strict lockdown measures that have kept many international students away still mean borders are open.

“Australia’s strict Covid restrictions have kept the death toll low,” he said – “and with the strength of the economy and overall outlook, it’s a safe and fun country to live in,” making Australia an attractive country to study. .

Despite the “background noise” of geopolitical tension, Green suggests that Chinese students will continue to play an important role in Australia’s higher education sector and funding. “It is like an iron table,” he says. “If someone said, ‘Let’s not talk to China,’ the economy would go upside down.” The same is true in higher education.”

[ad_2]

Source link