[ad_1]

A salty Louisiana breeze whips through Forrest Gomez’s hair as her team’s motorboat cuts through the warm waves of Barataria Bay. The inflatable Black Zodiac suddenly stopped next to a small fleet of ships, all dressed as floating labs.

Scientists in a boat cast a net into the water. With a net behind them, they drive in slow circles to catch their subject of study: a bottlenose dolphin.

“Go, jump now,” someone shouts. More than sixty marine mammals and helpers splash into the shoulder-deep water over the sides of the boats. They carry their weapons behind them as they go to Dolphin.

Gomez and the crew untied the animal, placed it in their midst, and prepared to perform several tests to assess its health.

Wildlife in Barataria Bay in southeast Louisiana on the Gulf of Mexico was among the worst affected by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. close to 200 million gallons of oilA BP rig that could fill 300 Olympic-sized swimming pools exploded and seeped into the Gulf, making it one of the worst environmental disasters in US history.

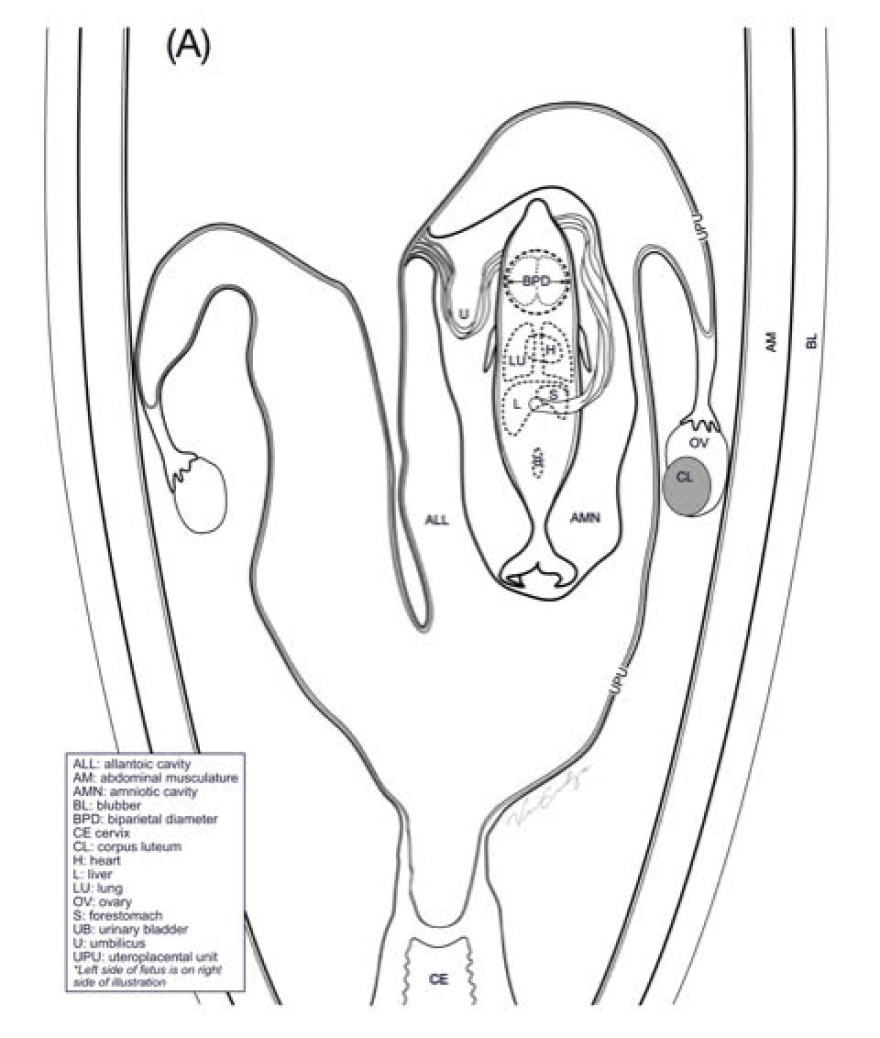

Gomez Barataria, medical director of the National Marine Mammal Foundation, used floating ultrasound machines to examine how the bay dolphin mothers were doing after the spill.

She wore sunglasses and a thick black hat so she could see the screen despite the bright sun. On it: a scan of an unborn baby dolphin. The water equivalent of the gel used on pregnant women’s abdomens makes it easier to get clear images.

National Marine Mammal Foundation

/

Dolphins, along with whales and porpoises, are among the “cetacea” marine mammals that carry seeds in their wombs and give birth to live young. Studies show Dolphins had a successful pregnancy only one-fifth of the time after spawning – a very low rate compared to two-thirds in healthy controls. Scientists think that oil can weaken the dolphins’ stress responses Immune systems And lungs make mothers more vulnerable to disease – and thus losing their babies.

“It’s a perfect storm,” Gomez said.

One of the health problems the dolphins have been facing in the 12 years since the oil spill is reproductive failure. However, the amount allocated to the risk – record 18.5 billion dollarsincluding a 5.5 billion dollars Penalties for violations of the Clean Water Act have led to unprecedented investment in new tools and science.

Long-term, focused research means scientists like Gomez have been able to. Describe the conditions of normal dolphin pregnancy. After more than a decade, her full-body ultrasound now takes just 10 minutes.

National Marine Mammal Foundation

/

Researchers hope to apply this knowledge to other marine mammals; Fertility is important for understanding population growth and decline. Such knowledge can inform conservation decisions or planning for emergencies, Gomez said.

“There’s no doubt that Deepwater Horizon accelerated many of these mechanisms,” Gomez said.

Veronica Cendejas

/

National Marine Mammal Foundation

All this new science will help us respond to future threats, from declining water quality to worsening red tides, researchers say. Because dolphins can experience the negative effects of polluted water first, what happens to them can happen to people along the way.

“Dolphins are custodians of ecosystem health,” said Randy Wells, director of the Chicago Zoological Society’s Sarasota Dolphin Research Program, who has studied dolphins for more than 50 years.

The question is whether humanity will continue to invest.

Assessing the damage

Bottlenose dolphins are just one of over 30 different dolphin species in the world. They can grow up to 13 feet or as long as a Volkswagen Beetle. In populations studied long-term, women are known to live up to 67 years and men up to 52 years, Wells said.

They show high intelligence and problem solving skills. Bottlenose dolphins have complex social interactions, and many live in resident communities, interacting with similar individuals over the course of their lives. Despite oil spills, hurricanes, or other threats to their environment, they tend to stay within their home range.

National Marine Mammal Foundation

/

Len Thomas once joined a team studying these dolphins in Barataria Bay. But after an ecological statistician from Scotland’s University of St Andrews sent a “frustrated statistician” scurrying back to dry land with a barb attached to his leg, he decided to keep the dolphin data safe from zoom calls.

Before the spill, baseline data on the dolphin population was scant, leaving little for researchers to analyze. After this, scientists had to measure the effect of the oil and make the government decide How much funding and rehabilitation was necessary.

It was a complicated process. According to Ryan Takeshita, a researcher who worked on damage assessment, a simple death count underestimates the damage.

“We didn’t just want to think about the dead dolphins,” said Takeshita, who now serves as deputy director of conservation medicine at the National Marine Mammal Foundation.

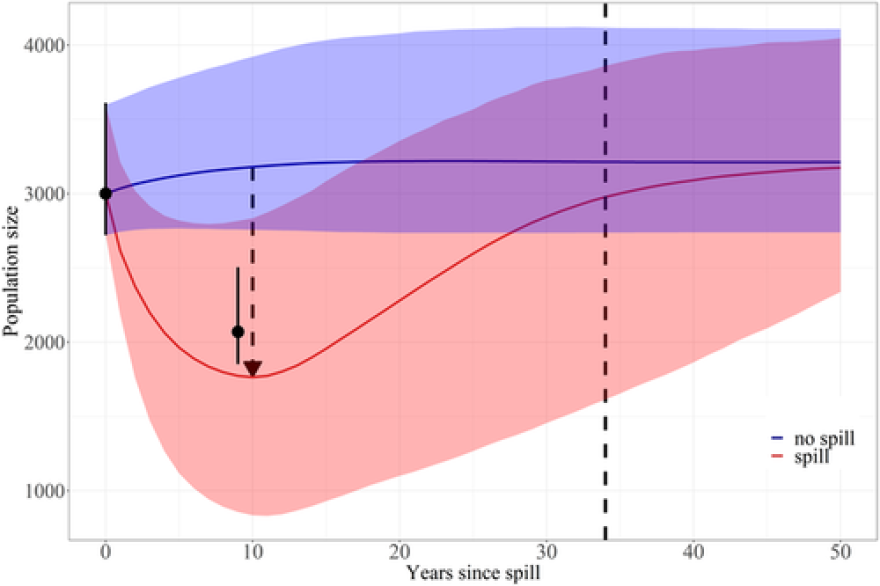

And while statistician Thomas predicts it will take 35 years for dolphins to recover to 95% of their original population, he wants more clarity on the impact of the spill.

Using data gathered from health assessments, Thomas came up with a population measure that provides a more accurate picture of dolphin recovery: cetacean years lost.

“Of all the people who could have been there, that’s the difference in years of experience,” Thomas explained.

The last number From his model: In addition to the more obvious damage, the spill killed 31,000 cetacean years.

“Now we have something that can be applied to basically any type of cetacean,” he said. “The modeling framework is there.”

In the future, Thomas hopes to see more baseline data so that marine mammal scientists can refer to it in the event of another disaster.

Bottle banging

Once the scientists get in the water, “it’s really like a well-organized circus,” said Barb Linehan, deputy director of animal health and welfare at the National Marine Mammal Foundation. The team works simultaneously to gather their information and get the dolphins moving as quickly as possible.

For Linhan, a cardiologist, this means developing new techniques to listen to dolphins’ heartbeats. Before the oil spill investigations, the hearts of wild dolphins had never been studied. There were no agreed criteria for cardiac monitoring.

“That foundation hasn’t been laid yet,” Linehan said.

After months of practice, Linhan’s team a The five minute method. Vets reach between the dolphin’s front fins and turn it on its side to get the best angle. They then used an extra-long waterproof stethoscope to listen to the dolphin’s heartbeat, or held an ultrasound wand connected to a floating yellow ECG machine to take internal images.

National Marine Mammal Foundation

/

of the group The study was published Barataria Bay dolphin hearts are rare. Compared to healthy wild dolphins in Sarasota Bay, the walls of the ventricles — the part of the heart that transports blood to the rest of the body — were thinner than normal, which may be related to oil pollution, Linnehan said.

By perfecting the techniques and applying them to other populations, Linehan’s team discovered another surprising fact: Most of the dolphins studied had harmless heart murmurs.

Dolphins have large, muscular hearts that pump blood at high speeds. Sometimes, this results in extra sounds or murmurs in their heartbeats, a phenomenon seen in other athletic mammals such as sled dogs, racehorses, and even human marathon runners.

Knowing that these grunts are normal is important for both traditional dolphin veterinarians and those studying future marine crises because it can help them prioritize more pressing issues, Linehan said.

In retrospect, Linehan said, scientists should have been studying the hearts of wild dolphins.

“It’s unfortunate that it takes massive environmental disasters like that to get people to really understand and care,” she said. But then we have to use that speed.

Swimming to distrust

The benefits of these many innovations are already clear.

For one, Thomas models are already used Measure possible outcomes It is a project intended to restore oil erosion caused by the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion. Some scientists think it will eventually reduce the salinity of the water.

Thomas predicts that this low salinity will be “absolutely devastating” for dolphins in Barataria Bay.

“This Deepwater Horizon looks like a walk in the park,” Thomas said. “If it continues year after year, it will effectively destroy the population.”

Although initial recovery funds from the Deepwater Horizon have run out, researchers stress the need for investment to continue such research.

In addition to monitoring the dolphins’ post-spill health, scientists like Gomez hope to pursue other critical projects such as rehabilitation and rescue efforts for captive animals.

“The money was significant, but the story is not over,” Gomez said.

According to Wells, Florida is fortunate not to have experienced the effects of a catastrophic oil spill comparable to Louisiana. A large amount of drilling On the Gulf Coast.

“It’s a fool’s errand to believe that nothing can go wrong,” Wells said.

Climate change poses another water quality threat, as pathogens survive longer in warmer water. Substances from agriculture, septic tanks and sewage infrastructure not designed to handle Florida’s rapidly growing population Continue to aggravate the red tide, killing dolphins and predators. Long-lasting pollutants and waste clog waterways.

“When pollution in the water is not controlled, it pushes ecosystems over the edge,” Wells said. “We need to give ecosystems a chance to bounce back.”

While dolphins may be at the forefront of these threats, Wells said, humans may feel some of the same effects. Dolphins and humans have common interests: we are mammals that depend on clean water for life.

This story is part of a series on UF’s College of Journalism and Communication. Drinking waterA Pulitzer Center-sponsored survey of statewide water quality in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act. Connected Beaches Reporting Initiative.

[ad_2]

Source link